The Sistahs

Top: Rosa Parks, Coretta Scott King, Condoleezza Rice, Maxine Waters, Jessie Redmon Fauset, Gwendolyn Brooks

Middle: Sojourner Truth, Madame C. J. Walker, Michelle Obama, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Maya Angelou

Bottom: Toni Morrison, Fanny Lou Hamer, Mae Jemison, Shirley Chisholm, Angela Davis, Harriet Tubman.

In the United States the month of March is recognized as “Women’s History Month.” The establishment of this month dates back to 1978 when a school district in Sonoma, California had a weeklong celebration on the accomplishments of women. In 1981, Congress passed a bill that proclaimed the week of March 7 as “Women’s History Week.” In 1987, after being petitioned by the National Women’s History Project, Congress passed a bill that designated the entire month of March as “Women’s History Month.”

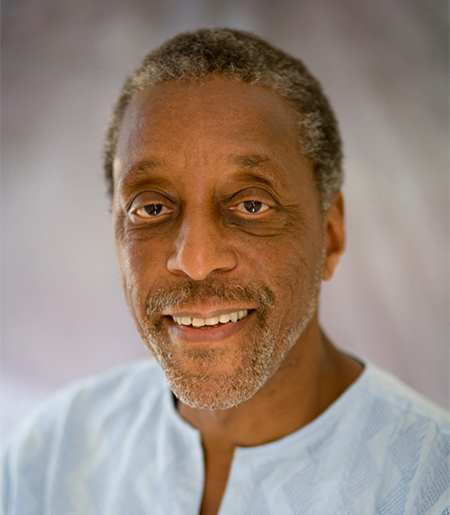

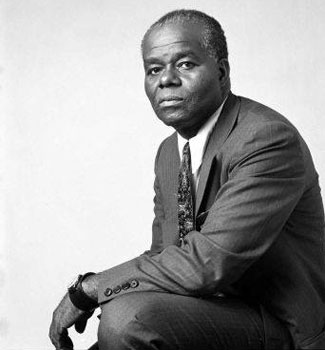

In recognition of Women’s History Month the Africana Library would like to highlight the portrait created by African American Ithacan artist, Khalil Bey. In 2014, inspired by the need for some female representation amongst the male portraits on display at Africana Library (John Henrik Clarke and Black cowboys Isom Dart, Nat Love and Bill Pickett), I asked Khalil to depict Black women that made significant contributions to American History. Khalil later told me, that when he began his research, he felt overwhelmed, as there were so many women to choose from. As a sports fan, I liken it to picking your favorite players from a team sport for an all-star game. Khalil ended up choosing 17 prominent women, and called the painting The Sistahs. I have to admit, Khalil picked a winning team.

In the painting Khalil has Michelle Obama, the first African American First Lady of the United States, in the center surrounded by a who’s who of women that contributed to politics and the arts. He even has three Cornelians in the painting: Jessie Redmon Fauset, Toni Morrison and Mae Jemison. Jessie Fauset, known as the “Midwife of the Harlem Renaissance,” was the literary editor for The Crisis, the journal of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Toni Morrison was a Nobel Prize- and Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, editor, professor and one of the best writers that America has ever produced. Former astronaut Mae Jemison became the first African American woman in space.

Some women in the painting are easy to identify, such as Rosa Parks. Parks is consider the spark that ignited the Montgomery Bus Boycott and in some circles, was nicked named the “mother of the Civil Rights Movement.” The Montgomery Bus Boycott lasted 13 months was lead by a 26-year-old minister, Martin Luther King, Jr. The boycott led to a United States Supreme Court ruling that stated segregation on public buses is unconstitutional. Coretta Scott King, the widow of Martin Luther King, Jr., is situated to the left of Parks. Coretta Scott King was dedicated to the civil rights movement and continued to fight for social justice long after MLK’s assassination.

Others portrayed in the painting are Condoleezza Rice, the first Black woman to serve as the United States National Security Adviser, as well as the first Black woman to serve as U.S. Secretary of State. Congresswoman Maxine Waters who is to the left of Rice, and is currently serving as the U.S. Representative for California’s 43rd congressional district. Waters is a member of the Democratic Party, is currently in her 15th term in the House. Gwendolyn Brooks rounds out the top row; it is as if she is watching over the other women in the painting. Brooks was a poet, author, and teacher. Her work often dealt with the plight of African Americans in her community. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1950, for the book Annie Allen. This made her the first African American to receive a Pulitzer Prize.

Sojourner Truth is the first woman in row two. Truth a former enslaved person from Ulster County, New York, is best known for being an abolitionist whose contemporaries were Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman. Tubman bookends Truth on the third row. In the words of historian Margaret Washington; “Harriet Tubman was the most daring, legendary, and courageous conductor on the human network of self-freed Blacks called the ‘Underground Railroad.’ A Civil War freedom fighter and woman suffrage advocate, African Americans called Tubman, Moses,’ symbolizing her premier leadership, and ‘Old Chariot,’ a term taken from spirituals she sang to alert the enslaved of her presence.”

Madame C. J. Walker who is positioned next to Sojourner Truth in the painting, is known as the first Black woman millionaire in the United States. She made her fortune from hair care products for Black women. Walker is also known as being a philanthropist and a political and social activist. In the same row next to Michelle Obama is Ida B. Wells-Barnett. I have to admit, Wells-Barnett is the person who first came to mind when I charged Khalil with doing the painting. She has so many accomplishments. Besides being an investigative journalist, educator and activist, she took up the led in the anti-lynching movement in the United States in the 1890s. She was a big inspiration to the NAACP in its fight to end lynching. It amazes me that it has taken almost 130 years since Well-Barnett first took up this fight, for the U.S. government to finally pass an anti-lynching bill in February 2020.

The person who rounds out the second row is Maya Angelou. She was an author, actress, screenwriter, dancer, poet and civil rights activist. Her memoir, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, stands out as the first nonfiction bestseller by an African American woman. I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings was first banned in 1996 for its profanity, violence, and sexual content. In the last row is Fannie Lou Hamer who is to the left of Toni Morrison in the painting. A former sharecropper, civil rights activist who is best known for the saying, “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.” But this active member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was a key leader in the civil rights movement. One of the best examples of her leadership came in 1964 when she took part in the founding of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), becoming vice chairperson and a member of its delegation to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey. In the last row Shirley Chisholm sits across from Hamer. Chisholm was a trailblazer in American politics. This Brooklynite was the first Black woman in Congress (1968) and the first woman and Black to seek the nomination for President of the United States from one of the two major political parties (1972). She ran as a Democrat.

Angela Davis is the final woman to be highlighted. Biographer Bettina Aptheker writes that “Davis has been internationally recognized as a leader in movements for peace, social justice, national liberation, and women’s equality. A scholar and prolific writer, Davis has published [12] books and scores of essays, commentaries, and reviews. Since the 1970s she has persevered in struggles to free political prisoners and to dismantle what she was the first to call the prison-industrial complex.”

The women depicted in this painting is an example of those who have achieved great things. They serve as an inspiration to us all. Which women would you choose to be recognized?

Sources:

History.com, Women’s History Month.

Library of Congress, Women’s History Month.

Washington, Margaret. Harriet Tubman.

Aptheker, Bettina. Angela Davis, Oxford African American Studies Center.

Additional Resources:

Angela Davis Resource Guide

Civil Rights Movement, Women

Edwidge Danticat Resources

Harriet Tubman Library Guide

Toni Morrison: Literary Icon

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela Guide

–Kofi Acree